Why is EU struggling with migrants and asylum?

- 40 minutes ago

- Europe

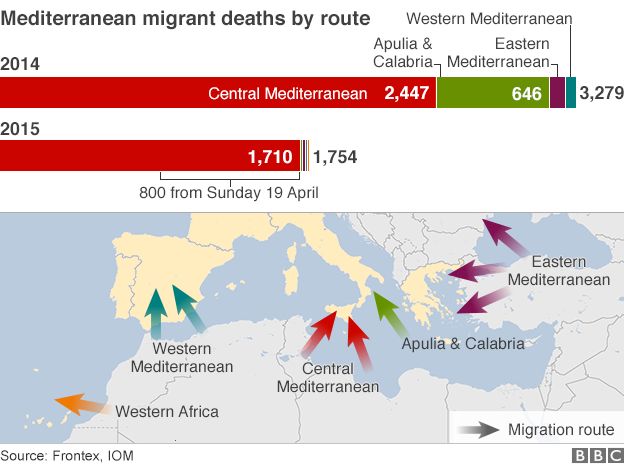

Hundreds of migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean this month, amid a surge in overcrowded boats heading for Europe from Libya.

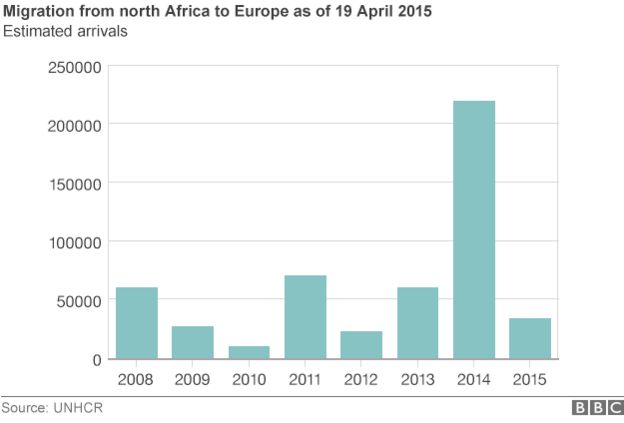

The flow of desperate migrants from North Africa hoping to reach Europe is already much higher than in the same period last year.

Italy is on the frontline and has urged its EU partners to do more to help.

At an emergency summit on 23 April EU leaders pledged to beef up the bloc's maritime patrols in the Mediterranean, disrupt people trafficking networks and capture and destroy boats before migrants board them.

However, any military action would have to conform with international law. The chaos in war-torn Libya remains a huge problem.

Championing the rights of poor migrants is difficult as the economic climate is still gloomy, many Europeans are unemployed and wary of foreign workers, and EU countries are divided over how to share the refugee burden.

How big is the migration challenge affecting Europe now?

The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) estimates that more than 21,000 migrants had reached the Italian coast between the start of the year and mid-April.

Survivors of the perilous voyage said they had suffered from violence and abuse by people traffickers. Many migrants pay thousands of dollars each to the traffickers, and robbery of migrants is also common.

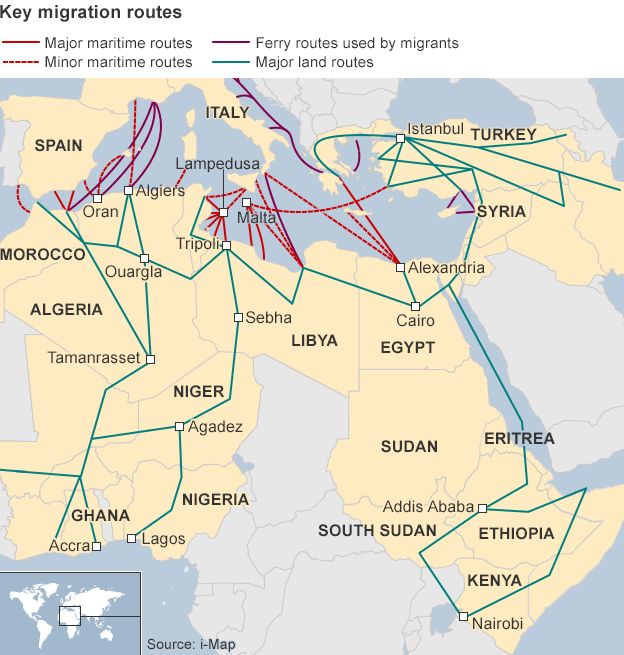

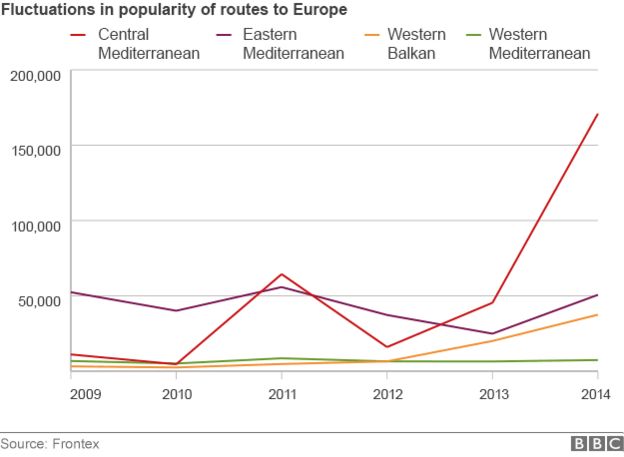

The main pressure point is the Central Mediterranean route.

On 21 April the UN refugee agency UNHCR reported that so far in 2015 a total of 36,390 migrants had reached Italy, Greece and Malta by sea.

It put the number of dead at 1,750 and missing at 1,776 - including those in the shipwreck on 19 April which claimed an estimated 800 lives.

The largest migrant group by nationality in 2015 is Syrians - 8,865 so far. Then come migrants from Eritrea (3,363), Somalia (2,908) and Afghanistan (2,371). Many of the others are sub-Saharan Africans.

In November 2014 Italy ended its search and rescue mission, called Mare Nostrum. It was replaced by a cheaper and more limited EU operation called Triton, focused on patrolling within 30 nautical miles of the Italian coast.

Aid organisations say the scaling down of the rescue effort has put more migrants' lives at risk.

EU leaders have now agreed to triple funding for Triton, to some €120m (£86m) - taking it back to the spending levels of Italy's Mare Nostrum.

Several EU member states have also promised more ships and other resources.

The vicious civil war in Syria has sent the numbers of Syrian migrants soaring. That is now the dominant feature of irregular migration to the EU.

Afghans, Eritreans and other nationalities are also fleeing poverty and human rights abuses.

Last year, some 219,000 refugees and other migrants crossed the Mediterranean, and at least 3,500 lives were lost, the UNHCR reports. In 2013 the total reaching Europe via the Mediterranean was much lower - about 60,000.

Back in 2011 the big challenge was thousands of Tunisians arriving at Italy's tiny island of Lampedusa. Far fewer Tunisians are making the voyage now, but Lampedusa remains a migrant bottleneck because it lies closer to North Africa than to Italy itself.

Migrant reception centres in Italy, Greece and Malta are overcrowded and under-resourced.

Why is Libya such a problem in the current crisis?

Two rival governments are battling for control of Libya, and so-called Islamic State militants have entered the country too.

The chaos has given people traffickers freedom to exploit migrants, with inadequate intervention from the authorities.

The EU and UN hope that a political agreement can be brokered to bring some stability to Libya, but so far there are few signs of progress.

There is great reluctance to send in any European military force.

What other routes do migrants take to enter the EU?

Data from the EU border agency Frontex records detections of illegal entries - it does not include the many migrants who manage to get in undetected.

Mainland Greece remains a major transit point - many migrants travel up through the Balkans, hoping to reach northern Europe. Neighbouring Bulgaria has seen a big increase in Syrian migrants entering from Turkey.

Before the 2011 Arab Spring the Western Mediterranean route was a big challenge for Spain, as many migrant boats arrived off the Canary Islands, carrying poor sub-Saharan Africans. The numbers dropped after Spain tightened co-operation with Morocco and fortified its North African enclaves - Ceuta and Melilla.

What has caused migrant numbers to rise?

The wars raging in Syria and Iraq are clearly big drivers of migration to Europe. Syria's Middle Eastern neighbours have taken in some three million refugees, while millions more are displaced inside Syria.

But many migrants also continue to make hazardous journeys from the Horn of Africa, often treated brutally by people traffickers and enduring desert heat and unrest in Libya, the main point of departure.

War has ravaged Somalia and Italian officials believe many of the migrants are genuine asylum seekers, fleeing persecution. In the case of Eritrea, it appears many are young men fleeing compulsory military service, which has been likened to slavery. Eritrea is blighted by political repression, human rights groups say.

Many Afghans continue to flee poverty and persecution in their country, as attacks by Taliban insurgents and criminal gangs remain widespread.

What about EU migrants?

It is important to remember that huge numbers of EU citizens move from one EU country to another freely. They are also described as "migrants", but they are fully protected by EU law, unless they are fugitive criminals. Their status is quite different from that of non-EU migrants. In some EU countries, including the UK, they have become an issue because of pressure on social services and competition for jobs.

Most EU countries are in the Schengen zone, which has made it much easier to cross borders without having to show a passport or other papers.

How is the EU handling the migrant problem?

For years the EU has been struggling to harmonise asylum policy. That is difficult with 28 member states, each with their own police force and judiciary.

More detailed joint rules have been brought in with the Common European Asylum System - but rules are one thing, putting them into practice EU-wide is another challenge.

The Dublin Regulation is a core principle for handling asylum claims in the EU. It says responsibility for examining the claim lies primarily with the member state which played the greatest part in the applicant's entry or residence in the EU. Often that is the first EU country that the migrant reached - but not always, as in many cases migrants want to be reunited with family members, for example in the UK or the Netherlands.

There are tensions in the EU over the Dublin Regulation - Greece complained that it was inundated with applications, as so many migrants arrived in Greece first. Finland and Germany are among several countries that have stopped sending migrants back to Greece.

The EU also has the Eurodac system - a common database of asylum seekers' fingerprints, which can be accessed under strict controls. Police use it to intercept false or multiple claims.

How do migrants get asylum status in the EU?

They have to satisfy the authorities that they are fleeing persecution and would face harm or even death if sent back to their country of origin.

The ban on mass "push-backs" - also known as "non-refoulement" - is an EU principle. In some cases it has not been respected, however. Greece, overburdened with asylum seekers, has been accused of refusing to let in some groups of migrants.

Under EU rules, an asylum seeker has the right to food, first aid and shelter in a reception centre. They should get an individual assessment of their needs. They can apply for asylum after giving fingerprints and being interviewed by a trained case worker. They may be granted asylum by the authorities at "first instance". If unsuccessful they can appeal against the decision in court, and may win.

Asylum seekers are supposed to be granted the right to a job within nine months of arrival.

The European Commission - the EU's executive - says there is still too much variation in the way EU states handle asylum claims.

How many asylum applications are successful?

The number of asylum claims in the EU rose to 626,065 in 2014, up from 435,190 in 2013, the European Commission reports. The 2014 figure is the highest since a peak in 1992, though back then the EU had fewer member states.

In 2014 the number of applicants from Syria more than doubled, compared with 2013, reaching 123,000. That was 20% of the total, and far above the next biggest group - Afghans, who accounted for 7%.

Migrants from Kosovo were in third place, just above Eritreans. Poor, marginalised Roma account for many of the migrants from Kosovo.

In 2014 asylum was granted to 163,000 people in first instance decisions - that is, nearly 45% of such decisions. But most EU countries still have backlogs of asylum claims to process.

The figure for asylum finally granted after appeal was much lower - 25,000 in 2013.

The figures for positive first instance decisions on asylum show Germany top in 2014 - 41,000, followed by Sweden (31,000) and Italy (21,000). The figure for the UK was 10,000.

0 comments:

Post a Comment